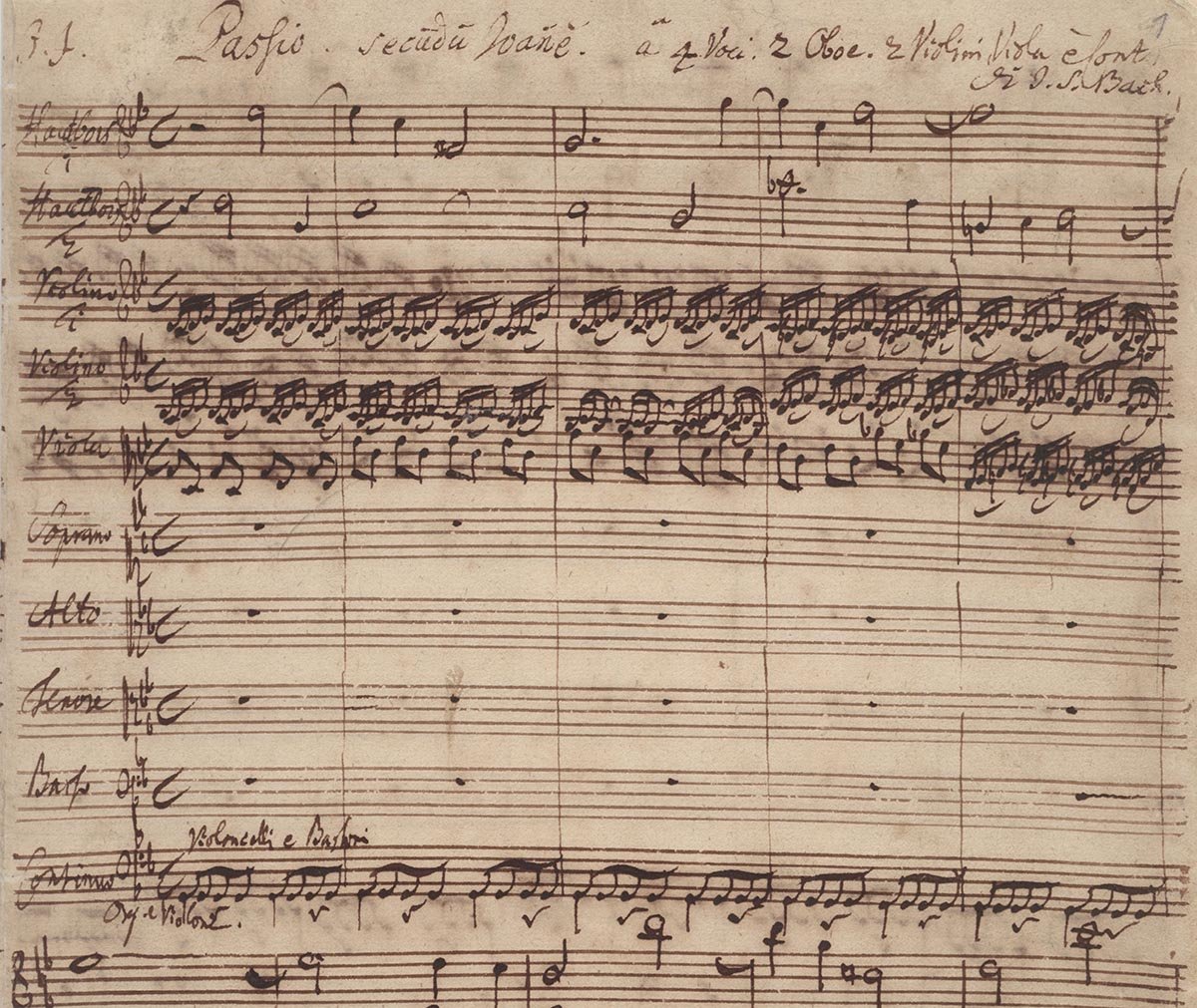

Into the Score: Bach St. John Passion

The heart of the matter: the solo arias

Bach’s St. John Passion opens and closes with extensive movements for chorus, with orchestra (the final chorus is followed by a chorale). In between, the musical material of the St. John Passion unfolds across several temporal planes, each with its own text type, purpose, and style.

One layer is that of the biblical narrative—the actual words from John, chapters 18 and 19, outlining the actions and conversations that make up the story. An “evangelist” (a tenor soloist) and other figures from the bible (Jesus, Pilate, et. al.), recite this prose, as music, in a form of heightened speech called recitative. Musically, this recitative layer comprises one solo voice at a time reciting the prose via melodies tracing and amplifying the contours of the words, supported by bass notes and chords from a continuo group—organ, cello, and bass, sometimes with lute or harpsichord. Where the biblical narrative includes a group of people (a crowd, a panel of high priests, etc.) saying something, Bach sets their words using the chorus (usually joined by the full orchestra). To reinforce the sense of multiples of people, these choruses are often contrapuntal, with staggered entries among the voice parts. The movements of this layer move quickly, as the action they’re portraying does.

Bach intermittently presses pause on the biblical narrative, slows down time, and steps aside from the immediate action in a second layer: solo arias. Here, the text is not biblical prose but highly emotive devotional poetry that reflects on some aspect of the action we’ve experienced. Musically, these atmospheric movements vary highly one to the next. Each has a specific instrumentation, tempo, and sense of gesture that, combined, enhance the emotion evoked in the poetry. These subjective movements, in first or second person perspective, helped Bach’s listeners interpret the narrative and incite their own devotion.

The remaining layer: chorales. These movements, sung by the chorus, accompanied by the full orchestra, present hymn tunes, harmonized in four parts, with poetic texts, set syllabically, in regular phrase groups. In Bach’s own church, the congregation likely would have sung along. Thus the chorales offer the community gathered a moment for collective contemplation.

Let’s zero in on that middle layer—the solo arias. It’s here that Bach deploys several instruments that weren’t regular participants in his orchestra, to expand the color palette and conjure distinct atmospheres. Some members of the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment and the Academy of Ancient music help us get acquainted with these special sounds, which the members of La Fiocco will share at PPM’s March 19 concert:

This video, introducing the baroque contrabassoon, begins with David Chatterton playing a passage from the last chorus of St. John Passion, “Ruht Wohl.” That movement bids: “rest well, you holy bones,” features an arpeggio to a low C, to represent “das Grab” (the grave). The C minor harmony takes on extra depth thanks to the double low C of the contrabassoon. (You can hear the low C at 0:24)

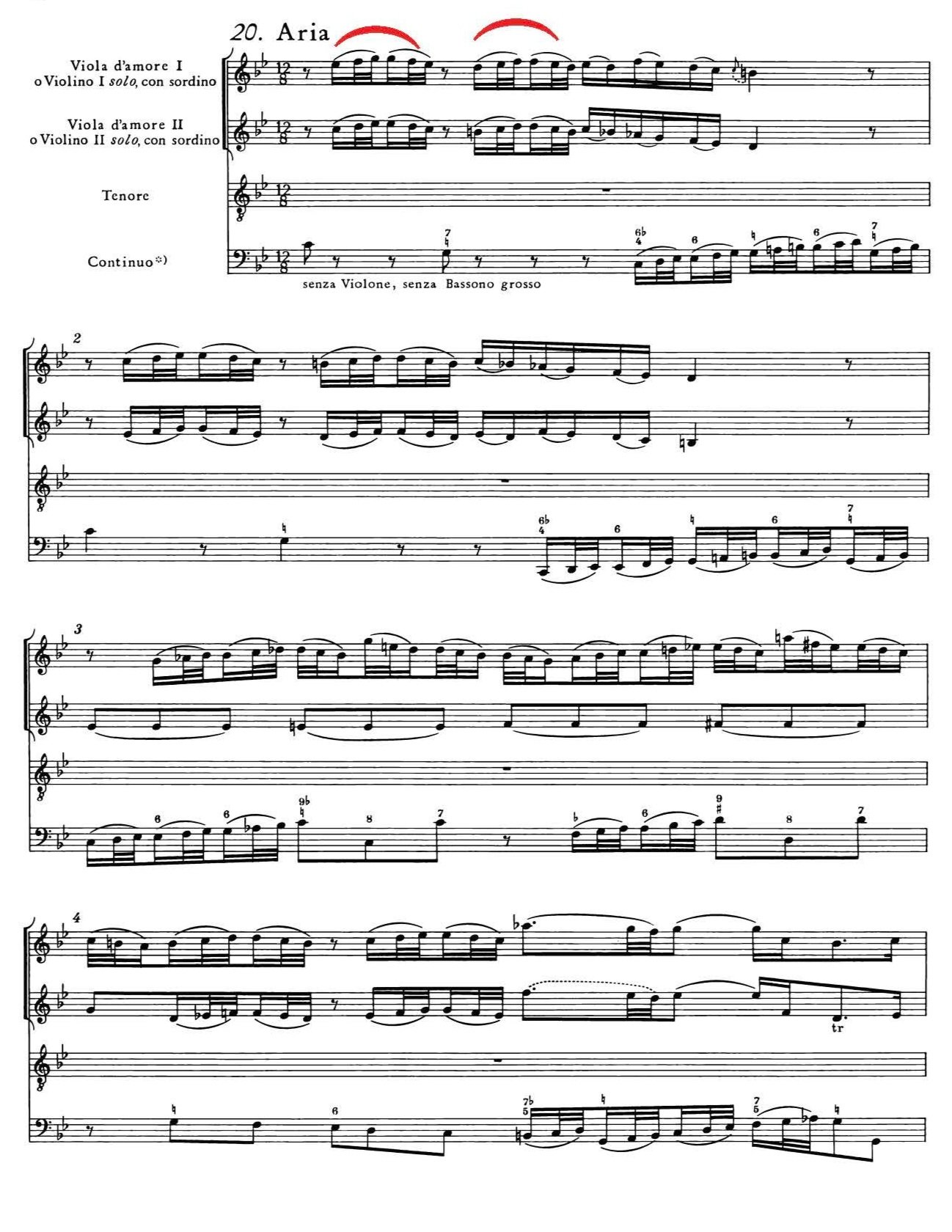

This video, featuring Pavlo Beznosiuk of the Academy of Ancient Music, begins with a passage from the tenor aria from St. John Passion, “Erwäge,” which accompanies the tenor solo with a duet played on viola d’amore. Pavlo introduces us to this extremely rare, beguiling instrument, which has not the usual four strings of the viola, but 12 or 14: six or seven strings played with a bow, and additional strings underneath the bowed strings, called “sympathetic strings,” which resonate glowingly while the strings above are played.

In this video, lutenist Elizabeth Kenny introduces the archlute—a comprehensive instrument that combines a guitar-like ability to strum chords with, thanks to a second, extended next, a series of long, powerful bass strings.

Of greater interest, even, than the instruments themselves is the way Bach puts them to use, in the solo arias. Let’s consider the arioso for solo bass, “Betrachte meine Seel” (“Contemplate, my soul”), and the tenor aria, “Erwäge” (“Consider”). This moment, in the biblical story, is the end of Chapter 18 and the very first line of Chapter 19. Pilate acknowledges a custom whereby he releases a prisoner, and the mob has insisted that the criminal Barabbas be released, not Jesus. So, Chapter 19 begins, Jesus is handed over to the Roman soldiers and is flogged—the first of several torments to be inflicted upon him. At this moment, Bach pauses the recitation of the biblical narrative for a moment of reflection—one of the longest in the work, the two solos lasting nearly eleven minutes together.

The opening chorus of the Passion establishes one of its principal themes, a paradox: that “Jesus, at the moment of greatest abasement, has become glorified.” This is that moment: Jesus tortured, his back ripped open in whipping, bloodied, is his moment of greatest degredation. And it is here that Bach, rather than turn away, horrified, from the tortured scene, pauses the objective reportage of John’s account for the subjective presence of soloists to Betrachte (“Contemplate”) and Erwäge (“Consider”).

ängstlichem Vergnügen – anxious pleasure

bittrer Lust – bitter joy

Dein höchstes Gut in Jesu Schmerzen – your highest good in Jesus’s suffering

auf Dornen so ihn stechen. . . Die Himmelsschlüsselblumen blühn – out of the thorns (on the crown of thorns) that pierce him, the Key-of-Heaven-flower (primrose) blooms

Du kannst viel süße Frucht von seiner Wermut brechen –you can pluck much sweet fruit from his wormwood

Let’s start at the level of the lyrics.

The poetry of both arias enacts the glorification heralded in the first aria, transfiguring the blood on Jesus’ wounded back into positive imagery. The arioso, Betrachte, continuing the sense of opposites/paradox, bids we “gaze without pause upon him” to find some semblance of gratitude amidst the gruesomeness, to re-conceptualize the pricks of the crown of thorns about to be placed on his head. The paradoxical metaphors abound:

Every musical parameter is calculated to convey these ideas.

At the outset, before the baritone has started, instrumentation and rhythm fashion an extraordinary atmosphere. The organ plays tasto solo, with no chords, leaving room for the delicate plucking of the lute (evoking the pricking of thorns), paired with the haloed sound of the violas d’amore. The movement from the lute contrasts the violas’ chain of suspensions, which, as the musical term suggests, suspends their sound across every first and third beat.

Melody and harmony amplify the imagery. “Ängstlichem” (anxious), “bittrer” (bitter), “schmerzen” (suffering), “Dornen” (thorns), and other anguished words are often approached melodically via a tritone—the most angular interval available (marked with a red TT, below), and enmeshed in dissonant, tightly-wound diminished harmonies (highlighted in yellow, below). At “blühn” (bloom) and “süsse Frucht” (sweet fruit), smooth melodies settle on relaxed, consonant harmonies.

Taken together, the ebb and flow perfectly conveys the text’s pairing of opposites.

Bach follows with an aria for tenor whose text likens the blurring blood and water on Jesus’s flayed back to the rainbow God creates as a sign of his covenant with Noah, after the flood.

Consider, how His blood-stained back

in every aspect

is like Heaven,

in which, after the watery deluge

was released upon our flood of sins,

the most beautiful rainbow

as God's sign of grace was placed!

Erwäge, wie sein blutgefärbter Rücken

In allen Stücken

Dem Himmel gleiche geht,

Daran, nachdem die Wasserwogen

Von unsrer Sündflut sich verzogen,

Der allerschönste Regenbogen

Als Gottes Gnadenzeichen steht!

The violas d’amore and viola da gamba take the dactylic musical figure of eighth note plus two sixteenth notes that was used as the melody for “whipped” and turn it upside down, into a rainbow shape. In the third measure, the second viola plays a pulsing chromatic line—Eb-E-F-F#—the “flood of sins.” Once again, Bach’s handling of all of the musical parameters powerfully convey the sense of the poetry, and give the listener more than seven minutes to “consider,” and seek salvation in the suffering of Jesus—a central theme of the work as a whole.

One sometimes overlooked feature of Bach’s church music, meant not as facile entertainment but as a conveyance of a biblical text and concomitant significance, is that it’s sometimes meant to be fiendishly difficult. The challenge is sometimes part of the aesthetic and religious experience. As for the exceedingly—yet beautiful—tenor aria, Erwäge, here’s what consummate interpreter and scholar of Bach, Sir John Eliot Gardiner, has to say:

Its exceptional difficulty for the singer is never a matter of oversight let alone willfulness on Bach’s part, but intrinsic to his philosophical purpose. The stupendous technical effort required by the tenor—with virtually no time to breathe—to emulate the mellifluous and weightless fluency of the superhuman violas demands that we ponder human fallibility. The dactylic motif sung by the Evangelist when describing Jesus’s scourging returns and permeates the entire aria—insistent enough to remind us that it is the weals on Jesus’s back that are here being evoked, but now softened and curved in such a way as to suggest that promised rainbow. Then, early in the B section, after the tenor sings the scourging rhythm for the first time and the instruments strain to delineate the “flood-waves of our sins’ deluge,” Bach parts the clouds and suddenly the rainbow miraculously appears. To bring this off in performance requires, besides stamina, imagination and a rock-solid technique, a combination of tensile strength and lyricism never easily achieved.

These are just two of the many beautiful arias, full of rich detail and variety, that provide moments for reflection in Bach’s St. John Passion. But, here at the heart of the work, is the heart of the matter. Bach saved some of his most exquisitely beautiful and anguished music for the moment of Jesus’s greatest suffering, and ensures that we have time to contemplate it before resuming the action of the story.